Page 9 - Iton 10

P. 9

Misrahi was religious, respectable and dull. Besides, I wanted action not prayer. Nor could I admit to him that

what first attracted me to this particular group was precisely their air of subversiveness, the very thing he

objected to.

I first saw them, one day, on my way home from school. A group of boys and girls, dressed like me in school

uniforms, walking just ahead of me. I instantly took to the careless manner in which they wore their uniforms,

with coats unbuttoned, caps jauntily tilted, all in defiance of the 'buttoned-up' manner in which officialdom

expected them to be worn. They walked side by side, deep in animated conversation, oblivious of everyone

else, as if the whole street belonged to them. Following close at their heels, to catch what they were saying,

I guessed, rightly, that they must be members of one of the Zionist youth groups I had lately read about in

the local Uj Kelet. Soon after, one of the boys from the group approached me and invited me to come to a

meeting; it seemed that they had noticed me too. My first meeting with the group confirmed my initial

impression of them as revolutionaries. The ideals of the movement instantly captivated my imagination.

Building a free and egalitarian society for Jews in Eretz Yisrael, promised a sort of hope for the future, and

a moral vindication, for which, (had I but known) I had been thirsting. No more ambivalent status of being

Hungarian-speaking Jews in a Rumanian state. We were Jews, and we were going to build our own Homeland.

With this one step we would leave the millennial curse of

anti-Semitism forever behind us.

My first direct experience of anti-Semitism, in its most

brutish and irrational form, was at the age of eight, when

the postman's daughter in Diciu threatened to kill me,

because, she said, I 'crucified Christ'! As I grew up, I learnt

to recognise in the behaviour of others the signs of hostility,

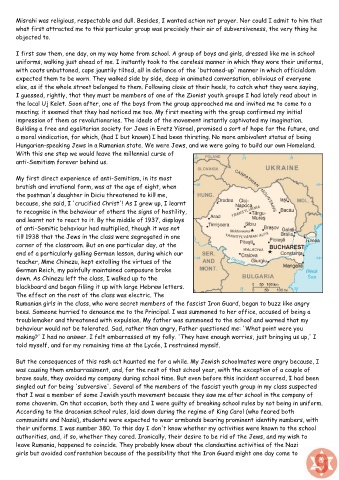

and learnt not to react to it. By the middle of 1937, displays

of anti-Semitic behaviour had multiplied, though it was not

till 1938 that the Jews in the class were segregated in one

corner of the classroom. But on one particular day, at the

end of a particularly galling German lesson, during which our

teacher, Mme Chinezu, kept extolling the virtues of the

German Reich, my painfully maintained composure broke

down. As Chinezu left the class, I walked up to the

blackboard and began filling it up with large Hebrew letters.

The effect on the rest of the class was electric. The

Rumanian girls in the class, who were secret members of the fascist Iron Guard, began to buzz like angry

bees. Someone hurried to denounce me to the Principal. I was summoned to her office, accused of being a

troublemaker and threatened with expulsion. My father was summoned to the school and warned that my

behaviour would not be tolerated. Sad, rather than angry, Father questioned me: 'What point were you

making?' I had no answer. I felt embarrassed at my folly. 'They have enough worries, just bringing us up,' I

told myself, and for my remaining time at the Lycée, I restrained myself.

But the consequences of this rash act haunted me for a while. My Jewish schoolmates were angry because, I

was causing them embarrassment, and, for the rest of that school year, with the exception of a couple of

brave souls, they avoided my company during school time. But even before this incident occurred, I had been

singled out for being 'subversive'. Several of the members of the fascist youth group in my class suspected

that I was a member of some Jewish youth movement because they saw me after school in the company of

some chaverim. On that occasion, both they and I were guilty of breaking school rules by not being in uniform.

According to the draconian school rules, laid down during the regime of King Carol (who feared both

communists and Nazis), students were expected to wear armbands bearing prominent identity numbers, with

their uniforms. I was number 380. To this day I don't know whether my activities were known to the school

authorities, and, if so, whether they cared. Ironically, their desire to be rid of the Jews, and my wish to

leave Rumania, happened to coincide. They probably knew about the clandestine activities of the Nazi

girls but avoided confrontation because of the possibility that the Iron Guard might one day come to